If you’re reading this, you’re probably an accomplished reader. In fact, you’ve most likely forgotten by now how much work it took you to learn to read in the first place. And you probably never think about what is happening in your brain when you’re reading that email from your boss or this month’s book club selection.

And yet, there’s nothing that plays a greater role in learning to read than a reading-ready brain.

As complex a task as reading is, thanks to developments in neuroscience and technology we are now able to target key learning centers in the brain and identify the areas and neural pathways the brain employs for reading. We not only understand why strong readers read well and struggling readers struggle, but we are also able to assist every kind of reader on the journey from early language acquisition to reading and comprehension—a journey that happens in the brain.

We begin to develop the language skills required for reading right from the first gurgles we make as babies. The sounds we encounter in our immediate environment as infants set language acquisition skills in motion, readying the brain for the structure of language-based communication, including reading.

Every time a baby hears speech, the brain is learning the rules of language that generalize, later, to reading. Even a simple nursery rhyme can help a baby's brain begin to make sound differentiations and create phonemic awareness, an essential building block for reading readiness. By the time a child is ready to read effectively, the brain has done a lot of work coordinating sounds to language, and is fully prepared to coordinate language to reading, and reading to comprehension.

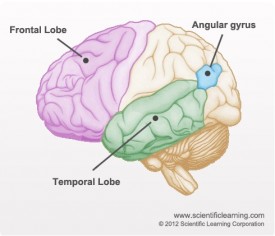

The reading brain can be likened to the real-time collaborative effort of a symphony orchestra, with various parts of the brain working together, like sections of instruments, to maximize our ability to decode the written text in front of us:

- The temporal lobe is responsible for phonological awareness and decoding/discriminating sounds.

- The frontal lobe handles speech production, reading fluency, grammatical usage, and comprehension, making it possible to understand simple and complex grammar in our native language.

- The angular and supramarginal gyrus serve as a "reading integrator" a conductor of sorts, linking the different parts of the brain together to execute the action of reading. These areas of the brain connect the letters c, a, and t to the word cat that we can then read aloud.

Emerging readers can build strong reading skills through focused, repetitive practice, preferably with exercises like those provided by the Fast ForWord program.

Independent research conducted at Stanford and Harvard demonstrated that Fast ForWord creates physical changes in the brain as it builds new connections and strengthens the neural pathways, specifically in the areas of reading. After just eight weeks of use, weak readers developed the brain activity patterns that resemble those of strong readers. And, as brain patterns changed, significant improvements for word reading, decoding, reading comprehension and language functions were also observed.

It’s never too early to set a child on the pathway to becoming a strong reader. And it’s never too late to help a struggling reader strengthen his or her brain to read more successfully and with greater enjoyment.

It’s all about the brain. Have you hugged your brain today?

Related Reading:

10 Ways to Help Your School-Age Child Develop a “Reading Brain”

Learn more about the Fast ForWord K-12 reading and language solution by downloading the info pack.

Awesome blog.Really thank you!

It's amazing how the brain functions. The key learning centers in the brain is responsible for helping us learn the art of reading and comprehension. There is alot of work taking place in the brain of a baby. The sounds that they hear is coodinating to the language that they will speak. It is important to read, sing and talk to babies while their brain is developing.

The temporal lobe, the frontal lobe and the angular and supramarginal gyrus all has it separate and unique functions.

This was a pretty interesting article. It talks about how we learn to read and what happens inside the brain. Which parts of the brain are responsible for the processes of reading. Reading is something that a lot of people take for granted because we do it without thinking about it. We do it so often and so quickly that we take for granted what actually happens inside the brain. I did not realize the different things that the Temporal lobe, Frontal lobe, Angular, and Supramarginal gyrus do to work together to enable a person to read. This article has a direct relation to the Poverty training we are going through at our district level. If we understand how kids learn to read we can make the connection with them in the classroom.

Has anyone studied if the problem for hyperlexic kids is "physical" and related to the Broca and Wenicke areas of the brain? These kids have struggle with listening and talking but excel in reading (I understand the brain used another area for decoding reding). Does it make sense they could have the two areas for speech damaged or underdeveloped and the area for reading supradeveloped? I believe the brain use a different area of the brain for learning foreign languages (vs area used for mother tongue). Is that correct? Could it be possible hyperlexics are using the foreign language area of neurotypical kids for learning their mother tongues?

Hi Caro! Thanks for your comment. Here is Dr. Burns' response:

A. Yes, Broca’s and Wernicke’s (language) areas have been investigated. See the following academic articles:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S014976341630639X

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0896627303008031

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24408490

B. The evidence suggests, if anything, that Wernicke’s area (superior temporal gyrus) is not damaged or underfunctioning, and may actually be overactive in hyperlexia, while the visual word form area (an area involved in letter recognition) is also very active—hence the ability to decode (match letters to sounds) (Ostrolenk et al., 2017).

C. Brain regions used for learning a foreign language overlap with the regions used for the native language: (See especially Wang et al., 2003) “Language-related areas including Broca’s area, Wernicke’s area, auditory cortex, and supplementary motor regions were active in all subjects before and after training and did not vary in average location. Across all subjects, improvements in performance were associated with an increase in the spatial extent of activation in left superior temporal gyrus (Brodmann’s area 22, putative Wernicke’s area), the emergence of activity in adjacent Brodmann’s area 42, and the emergence of activity in right inferior frontal gyrus (Brodmann’s area 44), a homologue of putative Broca’s area. These findings demonstrate a form of enrichment plasticity in which the early cortical effects of learning a tone-based second language involve both expansion of preexisting language-related areas and recruitment of additional cortical regions specialized for functions similar to the new language functions”

Wang, Y., Sereno, J. A., Jongman, A., & Hirsch, J. (2003). fMRI evidence for cortical modification during learning of Mandarin lexical tone. Journal of cognitive neuroscience, 15(7), 1019-1027.

D. The bottom line is that children with hyperlexia appear to be using some different areas of the brain than typical readers, but research suggests that these are not the regions used by foreign language users. Rather, they're regions associated with perceptual skills—especially visual form perception and auditory speech sound perception (Wernicke’s area).

I need to improve my comprehension. Thanks.

Thanks for your comment! Best of luck with improving your comprehension--you can do it!

I am seeking cause and direction for loss of ability to retain comprehension of written material. I have had issue with Arnold Chiara malformation and since decompression surgery I have regained many motor skills, but can not seem to retain what I read. I realize this is not directly related to this article, but trying (and failing)to find direction to address loss of reading comprehension.

Fast ForWord might be able to help you! It is a 2-in-1 reading and brain training program. You can find a certified Provider here: https://www.scilearn.com/national-provider-search/

So I was reading a brain teaser and I realised that I could easily read the words but when it came to recognising the color of the words my response got slower.. why is that???

The science of reading is both fascinating and complicated. It is noted that we develop pre-reading skills as soon as we begin to babble and coo in the infancy stages. This also would explain why children who are language deprived often struggle in pre-reading and reading. It is also interesting to learn that the science of reading is compared to a symphony production. All facets of the brain working together to make reading happen.

Before children can read, they need good vision and acuity. Most people think of vision as an eye function when it really takes place in the brain. Vision dysfunction can prohibit bright children from reading and it usually accompanies every other disability including dyslexia.

very interesting and useful information for us teachers of young students.

Thanks for your comment, Valerio!

Hey docan, I do extensive recitation and committing passages to memory, what part of the brain is benefited, would there be any injure ?

Thanks